White into Black: Seeing Race, Slavery, and Anti-Slavery in Antebellum America

Sarah L. Burns, Indiana University

Joshua Brown, The Graduate Center, CUNY

Noble or Savage?

Nothing seems as straightforward as a portrait, a picture of a person. We all have favorite photographs of ourselves—and back in the early nineteenth century Americans were crazy for portraits, too. With the invention of photography and availability of inexpensive paintings produced by traveling artists, Americans could own pictures of themselves. They also increasingly purchased pictures of famous people they admired (which were available as prints because photographs could not yet be reproduced).

But are all portraits the same? When does a “simple likeness” become a political statement?

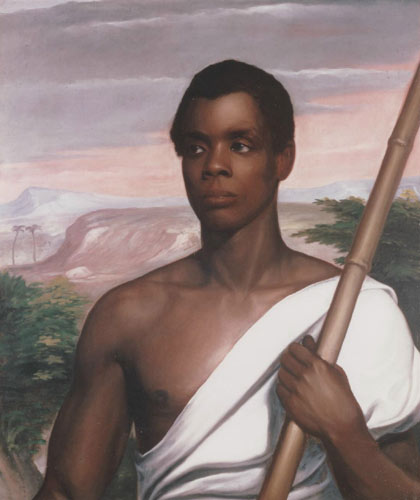

In 1839, a group of captive West Africans took over a Spanish slave ship called the Amistad. Led by Sengbeh Pieh, a Mendi from Sierra Leone (whose name was pronounced and spelled Cinqué by American friends and foes), the enslaved Africans killed the captain and ordered the Spanish owners to return the ship to their homeland. Instead, the Amistad was taken on a meandering course until waylaid by a U.S. navy ship. The Africans were charged with murder and jailed in New Haven. Abolitionists came to their support, including ex-President John Quincy Adams who represented them in court. While awaiting a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, Robert Purvis, a black abolitionist from Philadelphia, hired the New Haven painter and ardent abolitionist Nathaniel Jocelyn to celebrate the Amistad revolt’s leader and combat contemporary beliefs held by many Americans about African savagery. Duplicated in a print by Philadelphia engraver John Sartrain, the Amistad defense committee widely disseminated the portrait, which quickly became a powerful symbol of the cause and an oppressed people’s struggle for freedom.

Figure 10: Nathaniel Jocelyn, Cinqué. Oil on canvas, 30 1⁄4 x 25 1⁄2 inches, 1839. Source: New Haven Colony Historical Society.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 10: Nathaniel Jocelyn, Cinqué. Oil on canvas, 30 1⁄4 x 25 1⁄2 inches, 1839. Source: New Haven Colony Historical Society.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

First: Look at Figure 10. As you did with Powers’s Greek Slave, discuss your initial impressions of this painting. What did the artist want viewers to think about Cinqué? What aspects of the picture seem important in communicating those ideas? Why do you think the artist chose to portray Cinqué in this style of costume?

Second: Move your cursor over the portrait, examine the details, and read the accompanying information. Review your initial conclusions about what you thought was significant.

Third: Read the following two letters:

- Letter, dated February 29, 1841, from Cinqué to Lewis Tappan, a New York City businessman and abolitionist who organized the defense of the Amistad captives.

Dear Sir

Mr. Tappan,

I will write you a few lines because I love you very much and I will tell you about Mr. Pendleton keeper [of the jail in New Haven.] He will kill the Mendi people, he says all Mendi people. He want make all black people work for him and he tell bad lie. He says all black people no good, he whip them. He says Mendi men steal, he tell lie, he is wicked, very bad. He says Mendi people drink rum, he tell lie. All Pendleton children and his wife all do not love Mendi people. He go to Westville, he whip Mendi people, he whip Foolewa, he whip Kinna on Sunday morning, he whip these two men in New Haven he whip plenty of them in New Haven but me fear of for people, me fear for all good men in America Country. This keeper do bad to us, when he come from Washington he say he come from Havana, we shall [be?] sorry he say so, but me give you this letter. Pendleton his wife and his children, I think all bad, do not love God. When they come to Westville where Mendi people was they say stink, all stink here, but we sit still and I tell you one thing this. Better for Mendi people to go into Mr. Townsend’s house, better [than to?] go for wicked man’s house. When me live in wicked keeper’s house every day he whip Mendi people but we no love to whip Pendleton. He is bad keeper this wicked man. I do not like him at all, he is cruel. We love all every body that want make Mendi people free. Me like to go to Townsend’s house and give us good keeper, me like that better. But we do not like those who whip us, only we like the good man, those [who] do not whip us. Pendleton, he tell lie, I sorry for him. He say he give us clothes, he say Mr. Ludlow no good man for Mendi people, he say so. He say I kill plenty Mendi men before he die, he say so.

My friend, I want you to tell Mr. Adams about Pendleton he bad. The Lord God want all men to be good and love him, the Lord. Jesus Christ came down to make us turn from sins. He sent the Bible to do good on earth. My friend, I want you to pray to the great God to make us free and go our home and see our friend[s] in Mendi country. We want to see our friends in African Country and we shall pray to God to make our _____ very good and we want the God to have mercy on our friend[s].Your dear friends

Cinque -

Letter, dated April 14, 1841, published in the Pennsylvania Freeman, an aboltionist newspaper, after Jocelyn’s portrait of Cinqué was rejected from an exhibition of the Artists’ Fund Society in Philadelphia

Why is that portrait denied a place in that gallery? Any objection to the artist? No. He has been recently elected an honorary member of the society; and, if I mistake not, this rejected portrait was the principle means of procuring him that honor—if honor it be. Any objection to the execution? No. The “hanging committee” themselves pronounce it as “excellent work of art.” Those who are allowed to be judges in such matters rank it among the first portrait paintings of our country. Any objection to the character of Cinque? This could not be, for portraits of military heroes have been and are displayed in that gallery. He resisted those who would make him a slave by arms and blood. For doing this, did that committee exclude his portrait from their exhibition? Besides, he has been pronounced GUILTLESS in this deed by the highest tribunal of this country, and by the government of England. Was the portrait rejected because Cinque is a man in whom there is no interest? This could not be, for his name and his deeds have been heralded in every paper in this nation and in England—have stirred every heart and been the theme of every tongue. Though confined in a prison, he has been, the last eighteen months, an object of interest to the United States, to Spain, to England and to France. Cinque will continue to be an object of interest, and his name will be the watchword of freedom to Africa and her enslaved sons throughout the world.

Why then was the portrait rejected? Why? “Contrary to usage to display works of that character!” “The excitement of the times!” The plain English of it in, Cinque is a NEGRO. This is a Negro-hating and a negro-stealing nation. A slaveholding people.— The negro-haters of the north, and the negro-stealers of the south will not tolerate a portrait of a negro in a picture gallery. And such a negro! His dauntless look, as it appears on canvass, would make the goals of slaveholders quake. His portrait would be a standing anti-slavery lecture to slaveholders and their apologists. To have it in the gallery would lead to discussions about slavery and the “inalienable” rights of man, and convert every set of visiters into an anti-slavery meeting. So “the hanging committee” bowed their necks to the yoke and bared their backs to the scourge, installed slavery as doorkeeper to the gallery, carefully to exclude every thing that can speak of freedom and inalienable rights, and give offence to man-stealers!! Shame on them! Let the friends of humanity, of justice and right, remember them during the summer.

Had he looked into the future a little, J. Neagle would have sooner severed his hand from his body than have allowed it to sign his name to that note. Posterity will talk about him, when slavery is abolished, as it surely will be; and then all his fame, as an artist, will not save him from merited condemnation.

If Mr. Jocelyn is the man I think and hope he is, he will return his certificate of membership to the “Artist’s Fund Society,” counting it no honor to belong to a society that can perpetrate such meanings and outrage.

Thine.

C. WRIGHT

After examining the portrait’s details, reading about its symbols, and now reading these contemporary documents, what is your impression of the Cinqué portrait? Has your opinion changed from your first observation? Did the documents affect your views? If so, what do they reveal about the portrait that you did not first consider?

Do these documents revise your initial opinion about Jocelyn’s painting of Cinqué and its message? In what ways does that message confront or support beliefs about race and slavery in this period of U.S. history? Why abolitionists choose this image of Cinqué for distribution across the country?

Now compare the Cinqué portrait with Horatio Greenough’s sculpture of George Washington (Figure 11), which was commissioned by Congress and installed in the Capitol rotunda in 1841. Like The Greek Slave, this is an example of Neoclassicism, which the artist employed to make Washington heroic, godlike, and ideal.

Figure 11: Horatio Greenough, George Washington. Marble, 136 x 102 x 82 1/2 inches, 1840. Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Capitol, 1910.10.3.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 11: Horatio Greenough, George Washington. Marble, 136 x 102 x 82 1/2 inches, 1840. Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Capitol, 1910.10.3.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

What elements of the Neoclassical style are similar in Jocelyn’s portrait and what message about Cinqué do you think they reinforced?

Now examine the original seal of the Quaker-led Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (Figure 12), which, like its sister image seen in Step 1, was one of the most common and ubiquitous abolitionist symbols in both England and America, widely disseminated in pamphlets and broadsides and also worn in the form of bracelets, necklaces, and hair ornaments:

Figure 12: William Hackwood, Josiah Wedgwood, Am I Not a Man and a Brother? Jasperware medallion, 1 1/8 x 1 1/4 inches (oval), c. 1787. Source: American Philosophical Society.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 12: William Hackwood, Josiah Wedgwood, Am I Not a Man and a Brother? Jasperware medallion, 1 1/8 x 1 1/4 inches (oval), c. 1787. Source: American Philosophical Society.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Compare this image with the Cinqué portrait. How is the painting similar to and different from this popular anti-slavery symbol?

In 1841, the Supreme Court decided in favor of the “mutineers.” They were freed and the following year Cinqué and his compatriots returned to Africa.

It isn’t clear if the painting influenced the Supreme Court decision, but we do know that it inspired at least one other act of slave resistance. Purvis briefly sheltered a fugitive slave named Madison Washington. Washington was eventually recaptured and returned south, but he retained the memory of the Cinqué painting in his Philadelphia underground railroad haven. In fall 1841 he was sent from Hampton, Virginia, on the slave ship Creole, bound for New Orleans where he was to be resold. Reenacting the Amistad incident, Washington and his fellow captives sawed through their chains and took over the ship. They sailed the Creole to Nassau and, under British law, were granted asylum and freedom.

Does this story affect your overall impression of the painting?

At this point, you have discovered that there may be unspoken meanings in even such straightforward works of art as a portrait. These meanings must be taken into account to understand how seemingly “simple likenesses” were shaped and, in turn, affected the historical moment of their production and viewing. But, as we saw previously with The Greek Slave, no image exists by itself. Its meanings are in dialogue with—or inspire—other images.

With that in mind, look at these images. Discuss what you see in each one:

Figure 13: J. T. Zealy, Portrait of Renty, African-born slave Quarter-plate daguerreotype, March 1850.

Source: Peabody Museum, Harvard University Photo T1867.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 13: J. T. Zealy, Portrait of Renty, African-born slave Quarter-plate daguerreotype, March 1850.

Source: Peabody Museum, Harvard University Photo T1867.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

This is a photograph of “Renty,” (Figure 13) an enslaved man born in the Congo and, in 1850, owned by B. F. Taylor of Columbia, South Carolina. It is one of a series of daguerreotypes taken that March by photographer J. T. Zealy in his Columbia, South Carolina, studio of African-born slaves and their descendants from local plantations. The pictures were taken at the request of the Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz to substantiate the theory of the separate creation of the races, which provided a scientific rationale for racial slavery. Agassiz and his students used them for study and analysis. Kept in an archive, they were not seen in public until the twentieth century.

Figure 14: Ashanti Prince and Son, Gold Coast, 1820. Hand-colored lithograph, William Hutton, A Voyage to Africa, including a narrative of an embassy to one of the interior Kingdoms in the year 1820 (London 1821). Source: Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr.,The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 14: Ashanti Prince and Son, Gold Coast, 1820. Hand-colored lithograph, William Hutton, A Voyage to Africa, including a narrative of an embassy to one of the interior Kingdoms in the year 1820 (London 1821). Source: Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr.,The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

This illustration (Figure 14) shows Prince Adoom and his son, of the Ashanti Tribe on Africa’s Gold Coast. It was reproduced in William Hutton’s book, A Voyage to Africa, including a narrative of an embassy to one of the interior kingdoms in the year 1820 (published in London, 1821). Hutton was the British government’s consul to Ashanti, and his book offers detailed descriptions of Ashanti customs as seen (and judged) through upper-class British eyes. Prince Adoom was the nephew of the Ashanti king, and as Hutton described him, he is represented wearing the dress of the higher orders. Part travelogue and part diplomatic chronicle, Hutton’s book would have been read by well-educated people both in England and in the United States, where British books were imported in significant numbers.

You have probably noted that Prince Adoom’s attire and deportment is quite similar to that of Cinqué.

Now, examine these images. In a group or a whole class:

- How do you think each image (a daguerreotype and a book illustration) conveys—or does not convey—the same sort of views about slavery and/or race presented in the Cinqué portrait?

- Do you have different reactions to the nudity in the images of Cinqué, Washington, Renty, and the Ashanti prince? In what ways are your reactions similar to those you had to The Greek Slave?

- Do pose, drapery, context or setting in each example play a role in affecting how you think about each one?

- In which images do you think that the draping and exposure of the black body is ennobling, and in which is it degrading? In which is the figure made to seem inferior and primitive, and in which is the figure made to seem noble?

So far, we have been looking at images that by virtue of setting and dress remove their subjects from the modern, everyday Western world. But what about images that show contemporary, identifiable black figures arrayed and posed in modern fashionable dress? How did they convey messages about race, class, and individual character?