White into Black: Seeing Race, Slavery, and Anti-Slavery in Antebellum America

Sarah L. Burns, Indiana University

Joshua Brown, The Graduate Center, CUNY

White Slave or Black Slave?

When you look at images in history the old adage “seeing is believing” isn’t nearly as obvious as you’d expect: what people in the past saw and what they understood they were seeing may be hard to determine in the present–even with something that, at first glance, seems pretty straightforward, such as a representational statue.

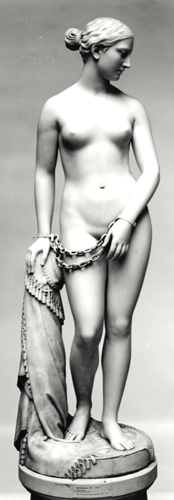

Figure 3: R. Thew, The Greek Slave in the Dusseldorf Gallery, New York City. Engraving, Cosmopolitan Art Journal, 2 (1858). Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 3: R. Thew, The Greek Slave in the Dusseldorf Gallery, New York City. Engraving, Cosmopolitan Art Journal, 2 (1858). Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Hiram Powers, an American sculptor in Florence, Italy, created The Greek Slave in 1844. The statue made its debut in England in 1845 and (in a second version) in the United States two years later. In 1851, it was one of the most highly acclaimed works on view at the Great Exhibition in London. Wherever it appeared, The Greek Slave (Figure 3) met with wild enthusiasm. It was one of the most famous and popular works of the time, and in reduced scale it was widely reproduced for display in the parlors of American middle-class homes.

The image represents a modern Greek woman who has been abducted from her home, stripped naked, shackled, and displayed on the auction block of a slave market in Constantinople during the era of the Greek war for independence from Turkey (1821-29). The statue is rendered in the Neoclassical style, which originated in the late eighteenth century when painters and sculptors looked to the example of ancient Greece and Rome in order to reform the art of their day. The dominant sculptural style in antebellum America, Neoclassicism with its dazzling white marble and sleek, smooth surfaces was used to represent ideal beauty, goodness, and perfection. At the time of The Greek Slave, many Americans considered nudity in art to be shocking and indecent. But in the hands of Hiram Powers, the Neoclassical style, which highlighted heroism and virtue, eliminated the sensual grossness many ascribed to the nude figure, and made The Greek Slave acceptable and even morally beneficial for its audience.

First: Look at the statue (above). What details do you notice that might be significant for interpretation of the figure?

Second: Now using the cursor, explore the statue and its details and read the accompanying information. Review your initial conclusions about what you thought was significant.

Third: Read the following pieces, which were typical of the praise heaped upon the Greek Slave when it went on view in American cities in 1847:

-

Review in the conservative New York newspaper, Courier and Enquirer, published on August 31, 1847.

THE GREEK SLAVE.—None of the many descriptions which we had heard and read of this statue gave us any idea of what we were to expect. All were but vague and unmeaning expressions of admiration, from which we could gather nothing save that their object was a beautiful woman with her wrists chained. We wondered at this, but having seen the statue, we wonder no longer; its beauty is so pure, so lofty, so sacred, takes such a clinging hold upon the heart, and so subdues the whole man, that time must pass before one could speak of its merits in detail without doing violence to the emotions awakened in him; and there are few, we think and hope, of the great number who have already seen this exquisite creation of the chisel who will not sympathize with us in this feeling. We cannot attempt, at present at least, to analyse the impressions which this lovely woman makes upon us, or to indicate in detail the many delicate beauties which go to make up the one great and almost oppressive beauty of her presence.

It is extremely interesting to watch the effect which the slave has upon all who come before it. Its presence is a magic circle within whose precincts all are held spell-bound and almost speechless. The gray-headed man, the youth, the matron and the maid, alike yield themselves to the magic of its power, and for many minutes gaze upon it in silent and reverential admiration, and so pure an atmosphere breathes round it that the eye of man beams only with reverent delight and the cheek of woman glows but with the fullness of emotion. Loud talking men are hushed into a silence at which they themselves wonder; those who come to speak learnedly and utter ecstasies of dilettantism slink into corners where alone they may silently gaze in pleasing penance for their audacity, and groups of women hover together as if to seek protection from the power of their own sex’s beauty.

On Thursday the statue was not open to the public, but the door was continually besieged by parties of three and four, of both ladies and gentlemen, who begged admission on the ground that they were to leave town on Friday, and many have postponed their departure for the West and South, merely that they might see the Greek Slave. Amply will they be repaid, and amply would they have been repaid had they made a pilgrimage from the furthest West to worship at that shrine of beauty.

-

Poem, “Hiram Power’s Greek Slave” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, a notable British Victorian poet who knew Powers as a fellow artist and expatriate in Florence

They say Ideal Beauty cannot enter

The house of anguish. On the threshold stands

An alien image with enshackled hands,

Called the Greek Slave! as if the artist meant her

(That passionless perfection which he lent her

Shadowed not darkened where the sill expands)

To so confront man’s crimes in different lands

With man’s ideal sense. Pierce to the center,

Art’s fiery finger! and break up ere long

The serfdom of this world! appeal, fair stone,

From God’s pure heights of beauty against man’s wrong!

Catch up in the divine face, not alone

East griefs but west, and strike and shame the strong,

By thunders of white silence, overthrown.

After examining the statue’s details, reading about its symbols, and now reading these contemporary observations, do this article and poem correspond to your own initial reaction to the statue or not? Based on the way they describe The Greek Slave, list what you think antebellum audiences did and did not want to see in this statue?

Contemporary observers commented in a variety of ways about Powers’s statue—and sometimes the most provocative commentary came from abroad. This cartoon in the British satirical weekly Punch used parody (commenting on an original work through humorous imitation) to emphasize certain meanings that many American admirers of The Greek Slave might have preferred to ignore.

The cartoon was called The Virginian Slave: Intended as a Comparison to Power’s [sic] “Greek Slave” and it was published in Punch in 1851 (figure 5). It was drawn by John Tenniel (1820-1914), who is best known today as the illustrator of the first edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice and Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass.

Let’s begin by looking at the cartoon. What details do you notice?

Figure 5: John Tenniel, The Virginian Slave: Intended as a Comparison to Power’s (sic) Greek Slave. Wood engraving, Punch, or the London Charivari, 20 (1851): 236. Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 5: John Tenniel, The Virginian Slave: Intended as a Comparison to Power’s (sic) Greek Slave. Wood engraving, Punch, or the London Charivari, 20 (1851): 236. Source: Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Now, let’s explore the cartoon (figure 6). Use your cursor to view the details up-close and read the accompanying information. After you have done this, review your initial conclusions about what you thought was significant

Next, compare the Punch cartoon with its inspiration, the Powers statue: list what elements the two images have in common, and what the Punch cartoonist changed. Why do you think Tenniel made these changes? List how those changes reveal the hidden meanings and messages that Powers’s statue communicated or implied.

What you have done so far is to discover that there may be unspoken meanings in works of art that must be taken into account to understand their significance. All works of art are also shaped by the historical moment of their production and viewing. But no image exists by itself, whether examples of fine art such as The Greek Slave or examples of popular art such as The Virginian Slave. Its meanings are in dialogue with—or inspire—other images.

With that in mind, look at these images. Discuss what you see in each one:

Figure 7: Unidentified artist, Painting of The Greek Slave with figures in oriental dress. Quarter plate daguerreotype, c. 1847. Source: Collection of W. Bruce Lundberg.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 7: Unidentified artist, Painting of The Greek Slave with figures in oriental dress. Quarter plate daguerreotype, c. 1847. Source: Collection of W. Bruce Lundberg.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

This retouched daguerreotype (figure 7), created by an unknown photographer about 1850, removed The Greek Slave from its idealized state and demonstrated how early photography became a medium for erotica. By tinting the nude figure in flesh tones and adding the leering, turbaned men in a Constantinople slave mart, the picture titillated viewers.

Figure 8: Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? Wood engraving, George Bourne, Slavery Illustrated in Its Effects upon Women (Boston, 1837).

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 8: Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? Wood engraving, George Bourne, Slavery Illustrated in Its Effects upon Women (Boston, 1837).

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

This illustration from an abolitionist book (figure 8) was a variation on the original 1787 seal of the British Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. The original organization symbol, showing a supplicant male slave, was designed by the famous British potter Josiah Wedgwood and in the form of cameos (a carved item of jewelry) became a popular personal expression of opposition to slavery in the United States.

Figure 9: Eyre Crowe, The Slave Auction, 1862. Oil on canvas, 13 x 21 inches. Source: Kennedy Galleries, Inc.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

Figure 9: Eyre Crowe, The Slave Auction, 1862. Oil on canvas, 13 x 21 inches. Source: Kennedy Galleries, Inc.

Use the slider to zoom in and out of the image

This 1862 painting, The Slave Auction, by the British artist Eyre Crowe (figure 9) was based on sketches he drew a decade earlier when he visited a slave market in Richmond, Virginia. Before Crowe rendered his memories on canvas, his drawings were reproduced and widely distributed during the 1850s in the British illustrated press.

Examine and reflect on each of the above images. In a group or in the whole class, discuss:

- What message or opinion does each image (a daguerreotype, a symbol, and a pictorial narrative of an event) convey–or not convey–about slavery?

- Do these images convey views about slavery similar to those presented in the Punch cartoon? Why or why not? How do you think viewers were meant to react to each image?

- In the first two images, both figures are nude and in chains. In each case, is the figure’s nudity idealizing or degrading? How can you tell?

- Does the inclusion of additional figures change or influence the way in which the message is communicated?

- Finally, how do the different media and different contexts of viewing affect the meaning of the respective images—the daguerreotype having one or a small number of viewers, the engraving reproduced in a publication having many subscribers, and a painting having numerous viewers when exhibited in a public space?

Reflecting back on our investigation so far, The Greek Slave has accumulated more meanings and connotations than first seemed apparent. Through close inspection of the statue’s details, attention to contemporary commentary about it, and comparison with other related images, you have identified both direct and implied meanings in the artwork that indicate a range of opinions about slavery in antebellum America.

But what about images that more explicitly expressed an anti-slavery message? Are their meanings simpler–or complicated in a different way?