White into Black: Seeing Race, Slavery, and Anti-Slavery in Antebellum America

Sarah L. Burns, Indiana University

Joshua Brown, The Graduate Center, CUNY

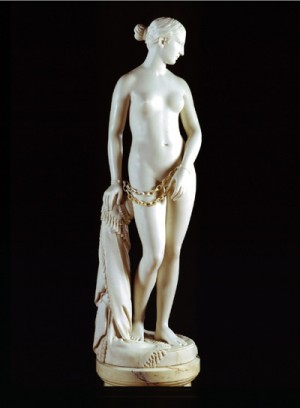

Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave, 1846.

Marble, 65 x 19-1/2 inches

Source: Corcoran Gallery of Art, Gift of William Wilson Corcoran, Accession Number 73.4.

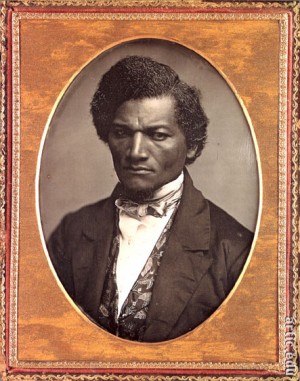

Samuel J. Miller, Frederick Douglass, 1847/52.

Daguerreotype, 5 1/2 x 4 1/8 inches.

Source: The Art Institute of Chicago, Major Acquisitions Centennial Endowment (1996.433).

What could these two images possibly have in common? They seem at first and even second glance to have no connection whatsoever: one is white, one black; one nude, the other clothed; one fictional, the other real. Yet there are ways to show that–appearances to the contrary–they are intimately and intricately related, and to learn what that relationship reveals about the meaning and function of art in antebellum or pre-Civil War America.

But to detect and understand these meanings, we need a set of strategies that will enable us to unpack visual images and decipher the explicit and implicit messages they communicated. In this “Lesson in Looking,” you will take a journey into the past where you will learn how to use those strategies to recapture a sense of how viewers in antebellum America understood visual images, and how they may have made connections that for us are now buried or unclear. By the end of the journey, you will understand the vital and dynamic role that visual images of every kind played in communicating ideas and shaping the ways in which people saw, thought, and acted in their time.

There are a number of ways you can use this “Lesson in Looking.” Supplemented by a brief essay on the historical background of slavery and abolition and another essay surveying the visual media of the era, this resource is divided into three steps. Together, these steps demonstrate how visual media shaped and were shaped by beliefs about slavery, race, and equality during the two decades preceding the Civil War. Following all three steps will take more than a standard class period, but will allow students to investigate the meaning, purpose, and structure of works of art in a range of media, and assist them in understanding how visual materials were viewed and used in the era. After examining several interactive images that model methods of observation and analysis, students will have the opportunity to offer their own interpretation of an archival picture. Suggestions for further reading and links to additional online resources will allow students to move beyond this lesson to apply their new insights and skills to other examples of visual evidence.

Depending on the class and its focus, there are other ways to use this resource. One step (assisted by the contextual essays, suggestions for further reading, and Web links) can work as the focus of a single-class activity. Or one step may be the focus of an in-class activity with the following steps reserved for a homework assignment. In short, this “Lesson in Looking” is designed to work in a number of permutations and to be useful in a range of classroom situations.