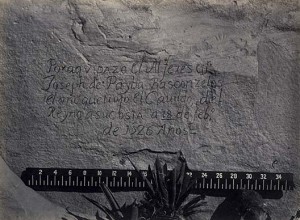

Timothy O’Sullivan, Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, 1873

Elizabeth Hutchinson, Barnard College

This image of an inscribed rock raises questions about the Spanish conquest of the American Southwest, post-Civil War western expansion, and the Frontier Thesis.

Timothy O’Sullivan, Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, South Side of Inscription Rock, N.M. No. 3, 1873.

Albumen print.

Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1994.91.137.

I’ve used this image in courses on American art history and the history of the West. It is an excellent companion to an exploration of westward expansion, as it both reminds students that the Anglo migrants weren’t the first to settle many areas in the West and helps them understand how post-Civil War expansion was caught up with the technologies and ambitions of modernity. I use it in a unit on the geological surveys, but have also paired it with Willa Cather’s novels. If teachers aren’t reading the marvelous prose of John Wesley Powell or Cather, I could see them using this image while discussing the transcontinental railroad as well as the Frontier Thesis.

Timothy O’Sullivan began his career as a photographer documenting the Civil War for Mathew Brady. Afterwards, he spent several years working for survey teams in the western United States. The assignments of each survey team differed, but in general they created maps and other documents of the West that would illustrate sites for future railroad construction and settlements, describe geology and natural resources, and provide information that would aid in the control of American Indians. If the Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican War mark the official U.S. acquisition of western lands, the surveys brought this land into the systems of knowledge that enabled its settlement and development.

This photograph was produced for Lt. George M. Wheeler’s survey of the 100th Meridian, which was dedicated to producing topographical maps or, as Wheeler put it, “the reduction and presentation of topography.” Photography historian Robin Kelsey has argued that O’Sullivan’s tendency to make photographs with shallow depth, strong horizontal composition, and an emphasis on geometric planes demonstrates a “visual affinity” between his work and the goals of the survey. This photograph has these qualities in the extreme.

But it is content as well as style that conveys the history of Western conquest. The Spanish text is an inscription left by Ensign Don Joseph de Paybe Basconzelos in 1726—“the year that he brought the City Council Body of the realm at his own expense.” Despite the difficulty of carving into a stone face, Basconzelos gave his letters a flourish that matches the self-importance of this claim, and by default characterizes the Spanish conquest as the heroic act of noble men. Superimposed on this is ruler whose regular lines and plain, Arabic numerals suggest the rational, bureaucratic nature of the American occupation of the West nearly 150 years later. Astute students will identify the camera as a tool with a similar dispassionate documentary capacity. Some will notice that O’Sullivan had to cut off the leaves of the yucca plant to expose the inscription, suggesting the violence that underscored this seemingly dispassionate conquest. However, the rock itself extends beyond the reach of the ruler, giving a potential monumental presence to this thing—the land, Nature—that the rational and graphic systems of these successive occupiers tried to conquer.

The power of the photograph is even stronger if students know something of the site where it was made in 1873: El Morro, also known as Inscription Rock, a sandstone bluff in western New Mexico. El Morro is known for being covered with pictographs left by people who had stopped there to drink from the water hole sheltered at its base during the past 2000 years. These include inscriptions by Don Juan de Oñate, who began the Spanish settlement of the Upper Rio Grande in 1598; General Don Diego de Vargas, who reconquered the region after the Pueblo revolt from 1680-92; and U.S. General Stephen Kearney, who occupied Santa Fe in 1846—making this rock a kind of autograph book for colonizers. Located at the top of El Morro are the remains of an Ancestral Pueblo settlement, and its inhabitants as well as Indians traveling between Acoma Pueblo to the west and the Rio Grande Pueblos to the east were among the first to mark their presence with pictographs of hands, animals, and other symbols, which probably inspired the later inscriptions. Prompted by the photograph and knowledge about the site, classroom discussion can extend to a comparison of Native and European attitudes toward land as well as a human relationship to nature.

References:

This photograph is in several collections, including the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the George Eastman House.

Robin E. Kelsey, “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey,” Art Bulletin (December 2003): 702-723.

Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), Chapter 3 (“Naming the View”).

Richard White, It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own: A New History of the American West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), Chaper 5.

For more on inscription rock, visit the El Morro National Monument.