Riis Redux: Seeing the Light

Vincent DiGirolamo, Baruch College, City University of New York

Jacob A. Riis’ photographs of New York’s lower east side at the turn of the twentieth century have become iconic images of immigrant poverty. Historian Vincent DiGirolamo uses them to teach students to look and think harder about photography as a tool of social reform.

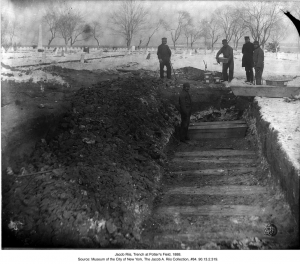

Jacob Riis, Trench at Potter’s Field, 1888.

Source: Museum of the City of New York, The Jacob A. Riis Collection, #84. 90.13.2.319.

The primary aim of art is to help us see the world anew. Yet familiar works, particularly photographs, take on an iconic quality that tends to confirm what we already know. Jacob Riis’ once shocking, insistently un-artistic photographs of urban squalor are some of the most iconic and oddly reassuring images of gilded age New York. It is all too easy for students to see his pictures of cramped tenements, begrimed immigrants, and ragged urchins, and think, “Yep, got it. Times were tough.”

I use two strategies to help them look and think harder. One is to hit them with a flurry of images from How the Other Half Lives in a slide show or PowerPoint presentation modeled after the “magic lantern” shows he presented in churches and auditoriums. Riis’s illustrated lectures were secular sermons about the horrors of slum life. Newspaper accounts and a stenographic report of one lecture allow us to replicate the order of his images and simulate the substance and spirit of his narration, including his tour guide’s mix of statistics and sensationalism, and his casual references to violent Celts, hot-headed Italians, haggling Jews, and cunning Chinese.

I end my talk as he did his, with the first picture he ever took – an overexposed photo of men (probably convicts and a guard) laying large and small coffins in a snowy trench in potter’s field. “What are you going to do about it?” he would ask his audience. The picture would then dissolve into the white outlines of a statue of Jesus, and Riis would quote from scriptures: “Even as ye do it unto the least of these….” I hope my version of his lecture conveys the power of photography as a new tool of social reform and evokes the influence of Christianity as a force for social justice. I want students to cringe at Riis’s ethnic stereotyping and yet appreciate his truly progressive view of poverty as a product of environment, not bloodlines.

My second strategy is to give students an opportunity to subject one of Riis’s images to a long, lingering look, and discuss what they see, think, and feel. They do this collectively in class or individually in essays. I either distribute my 8×10 glossies of Riis’s photos or direct them to published or online collections. To help them “notice what they notice,” I recommend four analytic approaches: sensory, formal, historical, and textual.

First, I ask them to divide the photograph in quadrants and take inventory of all they see in the four sections – objects, expressions, poses, and actions – and then note the most striking aspect or detail. I also ask them to “listen to” and “inhale” the photograph, imagining the possible sounds and smells of the scene.

Second, I urge them to note the image’s formal qualities – framing, composition, contrasts, values, vantage point, etc. to expand their vocabulary, I offer a handout or direct them to a website with a glossary of visual terms.

Third, I invite students to interrogate the image as historical evidence. I suggest they think about the picture’s age, authenticity, provenance, genre, subject matter, social uses, and ideological content, as well as its absences.

Finally, I ask them to investigate the tension between Riis’s words and images. What do his captions and commentary reveal about the moral and aesthetic choices he made as a writer and photographer? Are his descriptions value free or laden with inferences and theories? What categories did he impose on his subjects? Their answers are the beginnings of arguments, and the recognition of poverty as a patently real and artfully constructed social problem.

“Seeing is forgetting the name of the thing we are looking at,” said artist Robert Morris. My experience teaching Riis affirms this point. His photographs require more than a cursory glance, but can still inspire the kind of forgetting necessary to see the world anew.

References:

“Pictures from the Slums,” New York Sun (feb. 12, 1888).

“Stenographic Report of lecture titled ‘The Other Half and How They Live,’ delivered on 9 November 1891 in Washington, D.C., as part of the Proceedings of the Sixth Convention of Christian Workers in the United States and Canada,” Riis Papers, Library of Congress.

“Misery in the Slums,” Washington Post (Jan. 30, 1892), 2.

Jacob A. Riis, New York Tribune (Jan. 31, 1892).

Alexander Alland, Jacob A. Riis: Photographer and Citizen (Millerton, NY: Aperture, 1974).

Robert J. Doherty, The Complete Photographic Works of Jacob A. Riis (New York: Macmillan, 1981).

David Leviatin, “Framing the Poor: The Irresistibility of How the Other Half Lives,” Introduction to Jacob A. Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York (Boston: Bedford Books, 1996), 1-50.

“Basic Strategies in Reading Photographs,” 1998. http:/uovo.com/southern-images/analyses.html)