Irish Immigrant Stereotypes and American Racism

Kevin Kenny, Boston College

In this essay, Kevin Kenny examines a British political cartoon to raise questions about the transatlantic nature of anti-Irish prejudice and its relationship to the history of racism in America.

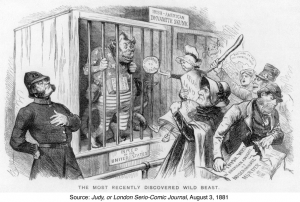

The Most Recently Discovered Wild Beast

Source: Judy, or The London Serio-Comic Journal, August 3, 1881

“The Most Recently Discovered Wild Beast” (1881) is one of a series of nineteenth-century images portraying the Irish as violent and subhuman. In the U.S. survey I use images of this sort when examining the history of anti-immigrant prejudice and its relationship to American racism.

Native-born Americans criticized Irish immigrants for their poverty and manners, their supposed laziness and lack of discipline, their public drinking style, their catholic religion, and their capacity for criminality and collective violence. in both words and pictures, critics of the Irish measured character by perceived physical appearance.

Political cartoons such as the “Wild Beast” offered an exaggerated version of these complaints. The Irish-American “Dynamite Skunk,” clad in patriotic stars and stripes, has diabolical ears and feet and he sports an extraordinary tail. around his waist he is wearing an “infernal machine,” a terrorist bomb that was usually disguised as a harmless everyday object, in this case a book. in the cage next to him, sketched in outline, is a second beast.

The Wild Beast image is especially interesting because it places American history in a transatlantic framework. the cartoon comes from a British satirical magazine called Judy and is part of a transatlantic discourse of anti-Irish prejudice. It captures a significant moment in Irish and Irish-American history known as the “New Departure,” which briefly united the main elements of Irish social and political protest in a powerful transatlantic coalition.

The United States was home to some of the leading Irish nationalists and social reformers, including Patrick Ford, the editor of the Irish World, a radical New York newspaper subtitled “An American Advocate of Indiscriminate Murder” in this image. Irish extremism, as the British saw it, was “Bred in the United States.”

Although the Wild Beast is an Irish-American, he is being held captive in Britain, as indicated by the figure of the policeman. The central action involves a girl held aloft to present the beast with a “Concession to Violence.” she represents the “Irish Land Bill,” a reform measure designed to defuse social tensions in Ireland. The nursemaid holding her aloft turns out to be Prime Minister William Gladstone, the chief supporter of the bill.

Gladstone’s appeasement of violence, the cartoon suggests, will only intensify Irish extremism. two figures in the image embody the loyal and moderate Irish – the woman in the background who addresses the beast in a typically Irish idiom (“Bad luck to ye! You murderin’ thief”) and the man to her left, brandishing a shillelagh. But Gladstone, his face set in stolid determination, is oblivious to his surroundings. And the policeman is so self-enamored that he has closed his eyes. British officialdom remains blissfully unaware of the consequences of making concessions to violence. Meanwhile, the Irishman to the right adds a sinister dimension to the proceedings.

This man is tearing up a copy of Patrick Ford’s Irish World, a significant source of inspiration and financial support for the Wild Beast. Yet his demeanor is more menacing than pacific; his action is violent, not moderate; and he moves furtively, with his back turned to Gladstone and the main action. He has the air of someone who has achieved just the outcome he wanted. In both posture and self-awareness, he neatly inverts the figure of the policeman, whom he otherwise resembles. Is he an Irish-American lurking within the crowd? Or an Irish resident of Britain newly inspired by American extremism? Either way he remains dangerously unobserved – except by the Wild Beast.

Beyond this Irish nationalist context, the Wild Beast image also needs to be interpreted with reference to the larger history of racism in American history. The form of prejudice on display here flourished from about 1845 to 1880, the period when Irish global migration reached its peak and Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species (1859). Ff gorillas were to be man’s closest relatives, then some breeds of men – especially the Irish – might at least be closer to the apes than others.

Crude versions of Darwinism offered a ready-made explanation for Irish violence in the United States. The New York City draft riots of 1863, the Molly Maguire case in Pennsylvania in the 1870s, and the exploits of Irish nationalists who, like the Wild Beast were prepared to use physical force to liberate Ireland from British rule – these events and many others called forth an explanation of Irish immigrants’ depravity that cast them as inherently violent, savage by nature. But was this really a discourse about race?

Some historians detect in anti-Irish prejudice a full-fledged racism of the kind endured by African-Americans. the Irish on both sides of the Atlantic were subject to vicious caricatures and stereotypes, to be sure. yet in neither Britain nor America did this prejudice translate into a system of racial subordination enshrined in law. Unlike African-Americans, the Irish could become citizens, vote, take legal suits, and move freely from place to place. In the end, then, images such as “The Wild Beast” tell us more about the middle-class creators and consumers of political cartoons than about how the Irish actually lived their lives.