Imaging Americans

Shawn Michelle Smith, School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Shawn Michelle Smith discusses Frances Benjamin Johnston’s photograph of Whittier primary school students as a historical inquiry into African-American education, citizenship, “uplift” campaigns, and visual propaganda.

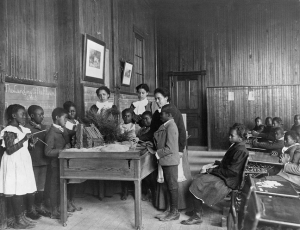

Frances Benjamin Johnston, Thanksgiving Day Lesson at Whittier, 1899

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Seven children crowd around a table at the front of a classroom. They are intent on a miniature log cabin placed at the edge of the tabletop. Several of the children hold thin joined pieces of wood that form the tiny cabin’s pitched roof. They seem to be waiting to make their contributions to its construction. Pressing close behind these children stand three adult women, presumably their teachers. Beyond this group at the front of the class, sit children at desks, with hands folded in their laps, or more theatrically propped on their desktops. Most of these children stare directly ahead at the activity in front of them, but two boys steal looks at the camera.

This is Frances Benjamin Johnston’s photograph of Whittier primary school students, made on commission in 1899 for the Paris Exposition of 1900. By the turn of the century, Johnston was a well-known photographer famous for her images of schools in Washington, D.C., and a favorite photographer to Teddy Roosevelt and his family. Hollis Burke Frissell, the second president of the Hampton Institute, an industrial arts school founded in 1868 to teach the formerly enslaved, invited Johnston, a white woman, to photograph Hampton and its satellite schools in Virginia, like Whittier, for the American Negro Exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition. The American Negro Exhibit was designed to show the progress African Americans had made since slavery, and its educational exhibits, such as those contributed by Hampton, were central to the uplift propaganda it espoused.

A number of things are striking about Johnston’s image. First there is the explicit performance of the students for the camera and for later viewers. The ring of children around the table has been opened up to give the photographer access to the scene. Most of the seated children cannot see what is taking place before them, as teachers and fellow students block their view of the table. Nevertheless, they perform attentiveness for the camera. Second there is the nature of this lesson. Written on the blackboard at the front of the classroom is the title “The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers.” This is a Thanksgiving Day lesson, in which young African American children are being taught a national history of Euro-American origins. They are being encouraged to identify as heirs of the “Pilgrim Fathers,” to anchor their American histories on the Mayflower, rather than on the slave ships that would have brought some of their ancestors to North America. Presumably they are building the cabin of pioneers, not of slaves or tenant farmers.

This subtle and complicated image opens onto many possible historical discussions about slavery, reconstruction, “uplift,” debates about African American education, assimilation, miscegenation, and visual propaganda. I have used it in American Studies and American literature courses to focus attention on the debates about African American education and uplift at the turn of the century. I have paired it with texts such as W. E. B. Du Bois’s “Talented Tenth” and “Of Our Spiritual Strivings,” and selections from Booker T. Washington’s autobiography, Up from Slavery. I provide background information about Hampton and Whittier schools, the photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston, and the American Negro Exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900, and then read the image carefully with students, asking: Who is represented? What is represented? What is the lesson, and how do we know it? What do you make of the way people are positioned in the photograph? How do you imagine the image was made? What do you think it was meant to communicate to its viewers in Paris? In the United States? At Hampton? What does it communicate to you?

I have found students to be very sophisticated interpreters of the image, noting its staged quality, the “caption” within the image written on the blackboard, the formal poses of the children seated at their desks, and the teachers crowding around the children at the front of the room. They have often surmised that the photograph was meant to depict young African American students as attentive and disciplined and patriotic, as worthy recipients of American education and citizenship. They have also questioned the nature of that education and the terms of national belonging, noting how the photograph appears to teach young African American students a lesson in Euro-American history that might not represent their own histories.