Two Views of a Dead Rabbit

Joshua Brown, The Graduate Center, City University of New York

This essay examines two images of members of an Irish street gang in the mid-nineteenth century that address issues of immigrant stereotyping, urban immigration, poverty, and reform in the wake of large-scale Irish immigration.

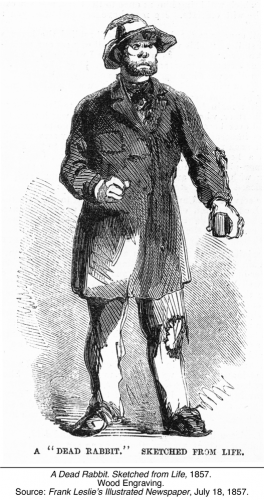

A Dead Rabbit. Sketched from Life, 1857.

Wood engraving.

Source: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 18, 1857.

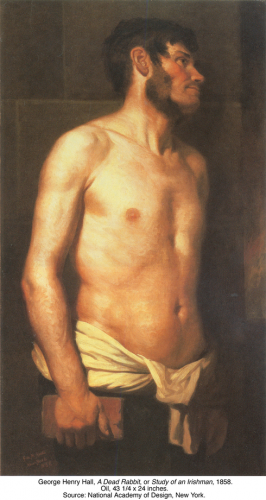

George Henry Hall, A Dead Rabbit, or Study of an Irishman, 1858.

Oil, 43 1/4 x 24 inches.

Source: National Academy of Design, New York

Thanks to Martin Scorsese’s 2003 film Gangs of New York, the subject of antebellum working-class Irish-American gangs is no longer obscure. Familiarity, though, doesn’t necessarily lead to enlightenment, and students have taken at face value the film’s many factual errors about poverty, immigration, politics, crime, rioting, and other facets of nineteenth-century urban history. Even the film’s visualization of the past is beset with problems, since it suggests a certitude regarding the “way things looked” while actually relying on a visual record that was shaped by contemporary prejudices about class, ethnicity, and urban poverty.

This is not the place to address the film’s historical distortions (click here for one historian’s assessment). But the visual depiction of urban immigration and poverty in the mid-nineteenth century is prevalent on the Web and students need assistance to interpret images that, in their style and substance, seem at first glance indecipherable or, worse, quaint. Juxtaposing two images may help orient students before sending them out on a foray through pictorial journalism, reform illustrations, political prints, cartoons, paintings, and photographs. These contrasting images, both rendered in the wake of a notorious New York City 1857 riot, are useful in getting students to look closely at visual documentary evidence while also helping them move beyond the sort of condescension toward and dismissal of the past that is often prompted by stereotypes and caricatures.

The July 4, 1857 Dead Rabbit-Bowery Boy Riot in the Five Points district of lower Manhattan is one of those rare occasions when the spotlight of national attention was cast on gangs, offering Americans, along with accurate and fanciful accounts of gang warfare, visual representations of these notorious urban denizens. As shown in the first image, an illustration that accompanied Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper‘s July 18, 1857 report on the riot, Irish “Dead Rabbit” gang members (in contrast to the ostensibly native-born “Bowery Boys”) bore the animalistic features that would become even more ubiquitous after the Civil War (most notoriously in Thomas Nast’s cartoons published in Harper’s Weekly). These grotesque, ape-like caricatures telegraphed the strangeness of the immigrants who had fled famine-wracked Ireland to inhabit the city’s streets. In their dress, public behavior, custom, and physical appearance, the Irish poor were seen and portrayed as another, dangerous species–or race, in an era where hierarchical beliefs equated nonwhite status with inferiority. Thus, elite New Yorkers such as George Templeton Strong could observe in his famous diary (using the racial measurement of the time) that, “Our Celtic fellow citizens are almost as remote from us in temperament and constitution as the Chinese.”

The Frank Leslie’s engraving conveys in succinct and cruel visual terms the dominant view of Irish immigrants in 1857; it also provides insight, in its depiction of the “Dead Rabbit”‘s clothes, about the dire poverty of some of the people who lived in the Five Points neighborhood. But does this and similar popular images from the period actually capture the way native-born, middle-class Americans saw their poor, foreign-born compatriots? Were perceptions in the past couched only in such stark and rigid terms?

An oil study by the New York-based genre painter George Henry Hall (1825-1913) offers us an unusual entrée into dominant attitudes toward the immigrant working class. Rendered shortly after the 1857 riot, Hall’s A Dead Rabbit (also called Study of an Irishman) depicts a mutton-chopped young man naked to the waist, cradling a brick in one hand while caught in a state of repose, a distant come-hither expression on his upturned face. With its relatively realistic portrayal of the male figure, its pose, and that brick, Hall’s picture captures an aspect of U.S. society and culture rarely shown in the era’s visual culture: the fear but also the fascination that fueled the class and ethnic conflicts of the mid-nineteenth century.

A Dead Rabbit is currently housed in the collection of the National Academy of Design in New York City. In 1882 Hall exchanged it for another work he had previously given the Academy, possibly because he had been unable to sell the painting in twenty-four years. Perhaps Hall’s picture was a little too insightful for the comfort of his nineteenth-century clientele.